There is a theory that has developed over the past few decades among anthropologists and historians that is known as “the stranger king theory.” What this theory tries to explain is why it is that throughout the world, and throughout history, we can find so many examples of people from one place who become the rulers of other places, that is, why people who are “strangers” to a given society, can become the “kings” of those societies.

In general, scholars have taken two approaches to answering this question. Some have emphasized cultural beliefs in the (mystical/divine) power of outsiders, while others have emphasized the practical role that outsiders can sometimes play. For instance, in some places where groups are at war with each other, sometimes a person from the outside can be more successful at maintaining the peace through his/her (perceived) position of neutrality.

David Henley, has argued for the value of the stranger king theory in Sulawesi, an area of what is today eastern Indonesia, and in 2006 he was the co-organizer of a symposium that invited scholars to examine this phenomenon in other parts of Southeast Asia and the world. A report on the symposium by Mary Somers Heidhues can be found here. A couple of years later some of the papers from the conference were published in a special issue of Indonesia and the Malay World 36 (2008).

In her report on the symposium, Mary Somers Heidhues wrote that “David Henley has speculated that the receptivity of the people of North Sulawesi to Dutch colonialism may have been motivated by a kind of stranger-king phenomenon, a willingness to accept foreign rule and rulers because the outsiders acted as impartial adjudicators in the many disputes that had previously typically led to outbreaks of violence. Supernatural prowess is another possible characteristic of stranger-kings, while others may win over followers by their facility in trade or special access to technology.”

The stranger king theory has been particularly used to talk about how Europeans gained colonial control over certain parts of the world. The theory argues that to some extent, and for various reasons, indigenous peoples allowed the European “stranger kings” to take control.

As Ian Caldwell and David Henley note in their introduction to the special issue of Indonesia and the Malay World, this theory would have been unspeakable in the 1950s-1970s “when a cresting wave of anticolonial nationalism. . . inclined even conservative scholars to downplay the role of foreigners,” but that “In our own era of multiculturalism, globalization, and the waning of egalitarian ideals, it has perhaps become easier to admit the historical importance of alien influences and elites alongside local genius and solidarity.”

It might be easier today for some scholars to “admit the historical importance of alien influences and elites” but most scholarship on Vietnamese history today is still about “local genius and solidarity,” because the “wave of anticolonial nationalism” has still not crested.

It’s too bad that that is the case, and it’s too bad that no one who works on Vietnam (or any of the mainland areas) was at this symposium because I think that places like the Red River Delta fit the stranger king model very well.

As is well known, the founders of two important medieval dynasties in the Red River Delta, the Lý and the Trần, both either came from, or were members of families that had come from, “China,” and the area of what is today Fujian Province in particular.

While this is well known, a great deal of effort gets expended in trying to explain away the foreignness of these people and to emphasize that either they had become local, or that even though they were from Fujian, they were not “Chinese” because there were non-“Chinese” people who lived in Fujian, etc.

This latter point is true, but it’s also true that one of the earliest kingdoms in Fujian, the Kingdom of Min/Mân, was established by one of those “Chinese” who had come from the north – a “stranger king.”

I think it makes perfect sense to argue that the Lý and the Trần were also founded by “stranger kings.” What is more, we can compare the situation in the Red River Delta with the countless other examples of stranger kings throughout the world throughout history to gain a sense of what type of stranger kings they were and what “model” of the stranger king phenomenon they fit.

Nationalist histories seek to show that a certain group is special. Non-nationalist histories identify phenomena that are common to human beings. Stranger kings are a common phenomena, and the Red River Delta is not an exceptional part of the world.

The founders of the Lý and the Trần were one form of stranger king, and it is therefore their “strangeness” that in part enabled them to become “kings” in the Red River Delta. We could learn a lot more about the history of that region of the world if we examined them as such.

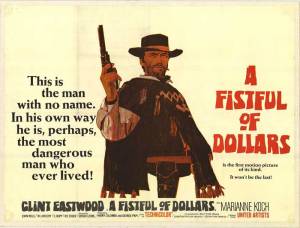

I’ve got pictures from what are known in the US as “Western” movies here because that genre relies heavily on a variation of the stranger king idea, the “stranger comes to town” theme. You have a town where there is some kind of trouble. A stranger comes to town. He ends up getting involved, sees who is really causing the problem, and “brings justice” to the town.

Historically there have been many places in the world were it took a “stranger” to bring peace and justice to an area. And in many ways, it was that person’s “strangeness” (whether that be a mystical power, an impartial outlook, or some combination of those elements) that enabled him to do so.

You made an interesting point here. Can you suggest, in what circumstances allowed those outside guys come to power in the Red River delta?

What is the proper explanation for these consequent events:

1009: Ly Cong Uan, an outsider, was supported to come to the throne.

Then, sixty years later, the same those people talked about “Southern river, mountain, southern king”

And then, another outsider from “the north” became king of “the south”.

What kind of value and identity those outsiders claimed and represented for? and why they could overcome the fear of the Red Delta river’s people toward the “north”?

Thank you !

The first thing we have to think about is who are “those people” that you mention.

Today in Vietnam (and much of the rest of the world) we have universal education (in a single language), mass produced textbooks (the content of which a centralized government to a large extent determines), and mass media, and ALL OF THIS is nationalistic.

1,000 years ago, NONE of that existed (including the concepts of “the nation” and “the people”). Yes, the poem that we now refer to as “Nam quoc son ha” was recorded in early texts like the Viet dien u linh tap and the Linh Nam chich quai liet truyen (although I think each of these works attributed that poem to a different time period – need to go back to check this). However, neither of those texts were ever published. It was also included in the Dai Viet su ky toan thu, but we have no evidence that a work like that was widely read. And then there is the fact that in all of these works that poem is attributed to a spirit, not to a human being.

So how important was the “Nam quoc son ha” ~1,000 years ago? I would say not very important. How many people knew about it? I would say not very many.

Further, whatever sense of being in “the south” existed, was also shared by educated people in the areas that are now Guangxi, Guangdong and Fujian provinces (works like the Ming-era Baiyue xianxian zhi [Record of the Previous Worthies of the Hundred Yue)] demonstrate this).

Finally, I think the difference that we imagine existed between say Ngo Quyen and Ly Cong Uan (if we accept that he came from Fujian) is exactly that – a difference that we are imagining. From Ly Bi onward my guess would be that the people we see as the elite in the region are people who if not intermarried with people from outside the region (i.e., from someplace in “China”), then they are culturally so similar to such people that there isn’t any perceivable difference between any of these people. Meanwhile, the difference between the elite in Fujian and the commoners there was just as extreme as the difference between the elite in the Red River Delta and the commoners in that region.

Having said all this, did the tiny elite who ruled over a kingdom in the Red River Delta want to be overthrown? Never, just as no rulers of any polity anywhere ever want to be overthrown. So the sense of wanting to remain in power must have been there, but that feeling was directed not just at “China” (as, starting in the 20th century, people have been taught to believe), but at any competitor for power, local or “foreign.”

So how do outsiders come to power in such situations? Well that’s exactly what the “stranger king theory” tries to explain, and there are many possible explanations. And I think the Ly and Tran are probably quite different.

My sense is that when the Tang Dynasty collapsed there were several potential “stranger kings” in the region. However, since the elite in the Red River Delta was already made up of people who had intermarried with people from Fujian/Guangdong etc. and/or were culturally very similar to the elite from Fujian/Guangdong etc., a “stranger king” like Ly Cong Uan was not really all that “strange.” It was a matter of degree.

In any case, the stranger king theory emphasizes two main “attractions” of a stranger king – 1) a sense that he has mystical/divine/special power or 2) a belief that as an outsider he can more fairly rule over people.

Then added to all of this is the fact that the stranger king might also use some force as well. But the reason why people came up with the stranger king theory is because they don’t believe that force alone can explain how such people come to power (European colonialists did not come to power merely because of force – local people usually played a very important role as well, and for various reasons).

So Ly Cong Uan might have been seen as special because of. . . his closer connections with that powerful cultural zone to the north. Or he may have been seen as someone who, as an outsider, could more fairly govern over the competing power groups in the region (and it’s completely obvious that the Red River Delta had been very divided up to that point). And of course, force was probably an element too.

A couple of hundred years later, how could the same thing happen again? My sense is that the Tran were probably one family among a much larger group of people who started to develop the coastal areas of the Red River Delta during the years of the Ly. Their trade connections, and their opening of new lands probably brought them wealth and probably some kind of “cultural capital” as well, as who knows, perhaps more Buddhists from places like Guangdong and Fujian were coming to the coastal areas, and that would have provided spiritual power to that area as well.

So while Ly Cong Uan may have been more of a “classic example” of a stranger king (I don’t think we can think of him as 1 person though, because he did reportedly have followers from Fujian with him), I think the Tran were a leading family of something bigger, and something that had been developing in the region for a longer period of time. Nonetheless, there was probably still something about them that was viewed as connected to the “outside” and it is that power/connection that perhaps led the Ly to associate themselves with the Tran (but that plan then backfired).

So the Tran probably don’t fit the “stranger king” model as well as Ly Cong Uan (or Thuc Phan), but I still think that the “foreignness” of the Tran was important, and in that sense it can be related to the stranger king model at a more general level.

I was born inside nationalist historiography…

Terrific, thanks for your response.

I was not aware enough of historical continuity before and after the 10th century in the Red River Delta. Reading Charles Holcombe on Southern Chinese empire during the Tang and try to connect what happened in northern Vietnam with the same phenomenon occurring at other centers stood at the edge of the Tang and Sung, things can be highly understandable. I think Liam C.K also makes some comparisons in his Biography of Hong Bang.

And then, another thing came to my mind.

There is a process of making “Han” in the history of the “Central kingdoms”. Peoples at the frontiers, if not run away, then became “Han” along the way of the imperial expansion.

Do you see the same paradigm in Vietnamese history: the process of making “Viet”? and if so, tracing back to, let say before 1500 /1850, what could be imagined and collective identities to justify “Viet”?

Thank you!

Liam CK? Is that Liam Calvin Klein? Isn’t that a fashion designer? Does he write about Vietnamese history too? Wow! That’s impressive!!

In the case of the Central Kingdom, we can see how non-Han peoples became Han (Jacob Tyler Whittaker, “Yi Identity and Confucian Empire: Indigenous Local Elites, Cultural Brokerage, and the Colonization of the Lu-ho Tribal Polity of Yunnan, 1174-1745” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of California Davis, 2008) because they left textual evidence of this process.

In Vietnam my sense is that there is some textual evidence that can show this happening to some extent with the Cham ruling elite, but politically I don’t think that’s a topic that anyone wants to touch at the moment.

One possible way to look at this would be to take a text like the Dai Viet su ky toan thu and try to “map out” where the “savages” (man 蠻) are. When “savages” are mentioned in the 12th century, where are they? When savages are mentioned in the 15th century, where are they?

This would be kind of difficult to do, because place names have changed (although the Kham dinh Viet su thong giam cuong muc does a good job of equating places mentioned in the DVSKTT with places in the 19th century), but it would be a good “digital history” project. Learn how to make maps with software like Quantum GIS (QGIS), and “map the savages.” It would be really interesting to see if this would reveal a “savage frontier” that moves over time.

As for collective identities, the only collective identities before the twentieth century were among the elite. If we were to go back to say the 18th century, then the only thing that the farmer in Village A would have known is that he was from Village A (and this was the case everywhere in the world).

Why would the elite have had a collective identity? I think Benedict Anderson talks about this in Imagined Communities. In becoming officials, the elite had to learn a lot of common things – including language – and once they became officials they moved around.

I think that if you combine that with what Richard A. O’Conner says about the way that certain types of agriculture produce common cultural traits: “Agricultural Change and Ethnic Succession in Southeast Asian States: A Case for Regional Anthropology,” Journal of Asian Studies 54.4 (1995): 968-996, then you can see how a collective identity could emerge among the elite.

If you read the Dong Khanh dia du chi, you can see that the people who compiled that work had no problem determining who in the kingdom was “Hán” and who was not “Hán.” So the elite could gain a collective sense of who the Hán were because they could see people who were more or less like themselves (and had become that way through their participation in the agricultural practices [with their accompanying rituals, and taxation, and contact with government officials] that O’Conner talks about). But as for the people in the villages whom the officials saw as “Hán,” they probably only knew that they were people of Village A or Village B.

I have a colleague here who works on India. When he went into villages in the 1980s (or maybe 1970s), people there didn’t know what “India” was. They’d never heard of it. I think that’s the norm. Peasants in “France” didn’t know what “France” was until a modern educational system was set up in the early 20th century and they were taught “who they are.”

The elite, however, could get some sense of a collective identity, but it is something that only they shared.

I like this idea of the stranger king, and think it would interesting to develop the idea of the French colonialists playing that role. While histories emphasize that there was a continuous indigenous rebellion from the moment that the French took control, in the overall scheme of things the resistance was limited and sporadic for many years. The majority of people were trying to keep themselves and their families alive — something that was probably difficult enough before and after the French.

You make three great points about why stranger kings might succeed: “1) a sense that he has mystical/divine/special power or 2) a belief that as an outsider he can more fairly rule over people.” and 3) force.

Wasn’t the mystical / divine / special power something that came to be called khoa học?

The French also created if not exactly a kind of fairness in their rule, a kind of security or pacification. One gets the idea that in the 19th century there were bandits and marauding forces that would occasionally plunder and pillage and generally add to the overall misery. But of course French rule was not entirely fair–it was too important to use the colony to economic advantage to be fair at all times. I suppose it was the lack of fairness, coupled with the nationalistic message that was facilitated by the infra-structure that the French built (shipping, trains, paved roads, newspapers, publishing industry, radio, etc) that lead to a local posse to the gunfight that eventually pushed the stranger king out of Dodge.

And could International Communism be a new stranger king as well that society had to assimilate to? Khoa học, dân tộc and biện chứng for their mystical powers. An ideal of độc lập tự do to suggest fairness. And as with the colonialists, plenty of force.

These are some really interesting points. I think the stranger king theory was developed to talk about times when there was really just one person who went somewhere and became king there. I think it can be expanded, but as it is, we have to think in more and more abstract terms. As we do, it dawns on me that we end up just talking about how anyone comes to power.

One of the things that the theory tries to point out is that people are complicit in their own conquest. And they don’t comply simply for self benefit, that is, we can’t simply label people “collaborators” or “supporters.” They agree to be ruled over for various reasons.

I’ve been looking at some stuff on North Borneo and thinking about this. The British had clear reasons for wanting to control the area. They were in many ways “allowed” to do that by the indigenous peoples (although some fought), but they didn’t have any idea of what the British were thinking (that they wanted to exploit the area economically). Some of what the British communicated (and I’m sure things got really altered through translation) made some kind of sense to people sometimes, but I’m not sure what they actually understood. I think that the spread of International Communism was somewhat like that in some places too (Shawn McHale wrote a bit about that in his book).

“First, we have to try to distance ourselves from the present, that is, we have to try to identify what is different about the way we think today, and we have to try to not use our present ideas to think about and explain the past.”

This is not to defend anachronistic history/propaganda concocted by an ethno-centric mind-set, but is the Western iconoclasm not also the result of an academic fashion of the day, a by-product of a certain social and professional environment that demands “ground-shaking, revolutionary, subversive” monographs every two to three years? Isn´t that the fallacy of all revolutionaries; that they believe to be in the possession of unblemished, superior knowledge and to be free of those misapprehensions under which everybody else is labouring? Are historical relativism and cosmopolitism not to be included if we are to rid ourselves of presentist idea[l]s?

I find the presumption that no “national sentiment” of some sort existed at all equally unfounded until proven. The problem probably lies in the question about what can be considered a proper nation. Is there any positive evidence for the assumption that people who lived in the Red River delta did not have an idea of being somehow connected, even if they didn´t know each other personally?

Taking an even older example; did Greeks and Romans, from the highest senator to the lowest soldier, not consider themselves to be living in communities distinct from other (ethnic) communities?

There might be some extreme cases as the ones mentioned about India and France. But I believe this to be an inadmissible generalisation to suggest this was the case at every time and everywhere.

Of course one could argue that the elite and intelligentsia considered themselves much more being members of a broader Chinese-inspired commonwealth. But that does not necessarily mean that ordinary people didn´t feel alienated by “foreign” lords. To say that the elite maybe didn´t care about or didn´t even feel a cultural difference and therefore tensions were low is to override the possible negative sentiment of “the people” with that of “the People that matter”, isn´t it?

“is the Western iconoclasm not also the result of an academic fashion of the day. . .” I agree with everything you say in that paragraph. And I often ask myself those questions.

However, there is one point that I keep coming back to. A couple of years ago I was reading some things on archaeological theory. I read about a bunch of different approaches, and then I read a critique of the approaches from the previous few decades (can’t remember when that article was written – 1990s or 2000s) in which the author pointed out that at the end of the day, the people who claimed to be using some “new” approach were ultimately all resorting to the same technique – “inferring to the best answer.”

In the absence of sufficient positive evidence, people were inferring answers that made “the most sense.” And the answers that they all felt made the most sense were the ones that could withstand the most counter-questions and counter-evidence.

In interacting with scholars from around the world, I can’t find anyone who doesn’t think this way. What seems to differ is the information/ideas that people have to ask counter-questions (and some of that in the West is the product of academic fads – but over time it also comes to be questioned in the same manner, but before that happens it can lead people in false directions).

At the moment I can’t find where I made that comment about “no national sentiment.” I remember writing it and thinking that it was too extreme and then adding “(as we think of it today),” and then I remember deleting that. Now I can’t find that statement, but my point in saying it was to provoke and push the Vietnamese who read this (and one person in particular who I was talking to) to do precisely what you say here “look for positive evidence.”

“Is there any positive evidence for the assumption that people who lived in the Red River delta did not have an idea of being somehow connected, even if they didn´t know each other personally.”

Nothing as clear as the India example. There is positive evidence to indicate that the elite did have a sense of being connected, however I can’t find positive evidence that indicates that commoners had that sense of connection. Meanwhile, there is positive evidence that shows that the elite saw certain people within their realm as “Others,” as “savages.” And there is a lot of positive evidence that counters/undermines the evidence that has been used to demonstrate the existence of a national identity/sentiment in the past.

There is an entire “cannon” of “evidence” (the “Nam quoc son ha” poem, the “Binh Ngo dai cao” etc.) that was “compiled” in the second half of the 20th century to argue for a coherent Vietnamese identity going back to at least the 10th century, and in many cases, people argue that it goes back to the first millennium BC. If you question the existence of that identity, this is the evidence that will be brought up time and again to “refute” such a position.

As I’ve argued extensively, and as the young Vietnamese scholars who can read classical Chinese that I know will agree, these documents do not show what people in the twentieth century have claimed they show (a national sentiment/identity that goes from, to use your expression about the Roman context, “highest senator to lowest soldier”). They have been taken out of their context, their meanings have been twisted, and they are thus not “positive evidence” of what people say they represent.

And I can’t find positive evidence to show that there was a national sentiment “from the highest senator to the lowest soldier” or a way for it to take hold.

How would the “lowest soldier” have known these things? How would that information have spread? The “national curriculum” was to study for the civil service exams which did not require knowledge of one’s own kingdom (some exam questions might ask about current matters in the kingdom, but one answered by talking about antiquity).

Vietnamese scholars have argued that scholars “told” peasants this stuff. I can’t find any positive evidence of this. I can, on the other hand, find positive evidence that demonstrates that prior to the twentieth century the elite looked down on the peasants and that it’s only in the second half of the twentieth century that peasants started to be seen as “the real people” (which is right at the same time that the cannon of evidence for national sentiment/identity was being created). But I can’t find evidence that people in a village far away from where the Trung Sisters’ temple is knew the story of the Trung Sisters prior to the twentieth century, for instance. I’ve researched about the “national hero,” Tran Hung Dao, and have found plenty of positive evidence to show that even the elite did not think of him in those terms prior to the 20th century. And I can’t find positive evidence that common people knew anything about him, except for the people around his temple in Hai Duong who saw him as a spirit who could cure women’s illnesses.

Finally, I should point out that in the 1950s in North Vietnam there was a scholarly effort to identify when the Vietnamese nation had emerged (the Soviets and Chinese had just asked the same questions). People argued back and forth and couldn’t come up to any conclusions. In part this is because they couldn’t decide on what constitutes a nation, and also because whatever criteria they used, they came up with contradictory conclusions. Then in the 1960s the war came and it was decided that the Vietnamese have had a common identity since the beginning of time. End of story.

So some of what I say here is exaggerated at times because the weight of ideas that were created for political reasons, and that have remained unchallenged for 30+ years, is immense and people who were “born inside nationalist historiography,” as one commenter said, need to be (I think) provoked and pushed a bit.

Ultimately I think that Anthony Smith’s idea that there were forms of ethnic sentiment that got transformed into national sentiment applies to the Red River Delta, but given the weight of the 30+-year-old cannon, it is extremely easy for people to simply fall back on the ideas from the cannon. So I’m pushing hard so that people (namely the young Vietnamese who read what I write here) won’t do that. You are certainly correct to point out (and I appreciate you doing so) that my claim that a national sentiment didn’t exist anywhere is untenable without evidence, but the other point you make, that the real issue is deciding what constitutes a “proper nation” is what I think is really important, and that is exactly what Vietnamese have not asked themselves since the 1950s.

There was something there prior to the 20th century, BUT 1) the evidence that we have so far indicates that it was the elite who maintained this sentiment/identity, 2) it wasn’t entirely “national” in that much of it was based on being part of a larger “Chinese-inspired commonwealth,” as you say 3) there is evidence of an awareness of regional differences, 4) there were people who were considered to be subjects of the kingdom but whom we can’t see the elite identify as being the same as themselves (Tai, Cham, etc.). . . this is a list that much more positive evidence can be added to. After we have done that, what will we be left with? I’m not sure but I think it will be able to withstand many more counter-questions than our current ideas.

Is doing so an act of “American/Western academic imperialism” (my expression)? It could be, and I honestly do ask myself that question a lot. Sometimes I think to myself that I should just be quiet and leave people alone, but 1) I’m too stubborn/stupid to do that, and 2) I find that people keep reading what I write. Ultimately I think that this is because they understand that many current ideas about the Vietnamese past do not withstand counter-questions very well (and I do receive a lot of positive evidence to support this interpretation). On the other hand, many of the people who think that way are young Vietnamese who are studying in “the West”. . . so maybe this is all just Western iconoclasm running amok. . .

Ok, I wrote too much here. In any case, I completely accept what you say (and thank you for keeping me honest) – I exaggerated. However, I would also like to take your “challenge” to what I wrote and direct it at everyone who talks/writes about a “national sentiment” in the Red River Delta in the past. Show us the positive evidence (and I would add – show us an argument that can withstand as many counter-questions and as much counter evidence as possible).

Other ” stranger kings ” in the history of other peoples :

_ When the Balkans were freed from Ottoman rule , Bulgaria or Rumania or both , I don’ t remenmber ,got bestowed from the western european big powers Saxony -Cobourg ( ? ) scion . It seems most “cavalier ” from the westerners or in modern parlance ” colonialistic ” . How come the locals accepted that ?

_ Sweden’s king in 1810 died without heir . How come the Swedish ruling

class decide among others candidates upon French general and Napoleon underling Bernadotte to become their king ? What did they hope to get from him , some kind of protection ? he didn’t seem to have much political influence in France or elsewhere ? Was he a Freemason ?

Thanks for the comments. Your question about “how come the locals accepted” a situation where they were ruled by a foreigner is exactly what the stranger king theory tries to explain. The gist is that people see benefit in one way or another in having the foreign person rule.

The difficult part is trying to figure out what it is that local people would have seen as beneficial.

This information about the stranger king theory from Wikipedia is actually pretty good:

“The Stranger King theory offers a framework to understand global colonialism. It seeks to explain the apparent ease whereby many indigenous peoples subjugated themselves to an alien colonial power and places state formation by colonial powers within the continuum of earlier, similar but indigenous processes.

“It highlights the imposition of colonialism not as the result of the breaking of the spirit of local communities by brute force, or as reflecting an ignorant peasantry’s acquiescence in the lies of its self-interested leaders, but as a people’s rational and productive acceptance of an opportunity offered.”

Another Chinese origin dynasty was the Ho dynasty. The ancestors of the Ho came from Zhejiang province and straightforwardly declared themselves of Chinese lineage. They traced their descent back to the Chinese Emperor Shun so nationalists cannot engage in revisionism and claim that they were non-Han “Baiyue” natives of Zhejiang.

An Dương Vương the King of Âu Lạc is said to have originated from the state of Shu in modern day Sichuan.

Lý Nam Đế’s family originated from Han dynasty China and fled down to Vietnam during the Wang Mang interregnum.

Many of the Kings of Min in Fujian were of Han Chinese origin of northern China. The first Kings of Yue and Minyue claimed descent from Yu the Great, the Chinese King from the Yellow River in the heartland of Chinese civilization.

The founder of the Kingdom of Min was Wang Shenzhi and he originated from Henan province near the Yellow River.

The founder of Nanyue was Zhao Tuo who was all the way from Hebei from northern China.

The native Baiyue people of southern China were not related to the Vietnamese anyway. They were Tai-Kadai, Hmong-Mien and possibly Austronesian. The natives of Guangxi immediately north of Vietnam are the Tai speaking Zhuang people.

So I don’t see why Vietnamese nationalists attempt to in these revisionist exercises, the Kings are clearly all non-Vietnamese, non Kinh.

Jizi was said to be a member of the Shang dynasty of China who moved to Korea and founded the Kingdom of Gojoseon. Wiman is another Chinese origin person who is said to have usurped the throne of Gojoseon.

Following the rise of modern ultra-nationalism in Korea in the 20th century and revisionists like Shin Chaeho these traditional accounts were attacked and needless to say not popular among nationalist Koreans.

In Islamic South-east Asia, Arab Sadah (descendants of the prophet Muhammad) from Yemen established Sultanates among Muslims peoples like the Malays and Tausug because their ancestry is prestigious in the Islamic religion.

Thanks for the comment, and I couldn’t agree with you more about this. Nationalism has created the idea that we are supposed to be ruled over by “our people,” but it would be interesting to “quantify” history, as I think that we would find that being ruled by people who were not “our people” could be the norm.

You could continue your list in Europe, for instance, where many monarchs were “foreigners.”

Le Minh Khai, where is your source for claiming that the Ly Dynasty was from Fujian?