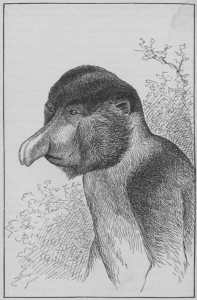

I was recently in Sabah, on the island of Borneo, were someone told me that the local name (in Malay) for proboscis monkeys is “blanda” (or “orang blanda”) which means “Dutchman.”

I laughed when I heard this, as there does seem to be a bit of a resemblance. . . But it made me wonder how such a term came to be used. Today I think many of us would like to imagine that Malay-speaking peoples on the island of Borneo started to call proboscis monkeys “Dutchmen” at some time in the past as a way to “resist” or “talk back to” the power of these Europeans who were conquering and colonizing parts of the region.

In reading a wonderful new book on the history of Western writings about, and representations of, the orangutan, however, I have come to realize that the situation in which the proboscis monkey came to be known as a “Dutchman” was probably much more complex than this.

This book – Wild Man From Borneo: A Cultural History of the Orangutan (University of Hawaii Press, 2014) – was written by an historian (Robert Cribb), a professor of theater (Helen Gilbert), and an scholar of postcolonial theory and literary studies (Helen Tiffin). In combining insights from their diverse areas of expertise, these three scholars have created a fascinatingly rich and illuminating work.

While these authors reveal that an enormous number of writings about the orangutan have been produced over the past few centuries, they argue that by contrast, “In their tropical homelands, however, orangutans appear to have attracted much less attention from indigenous people than they did from Europeans.” (5)

This might seem like an exaggeration, but their discussion about the origin of the term “orang utan” (or “orang hutan”), which in Malay/Indonesian literally means “man [of the] forest,” made me think about this issue.

These authors trace this term to some writings by Dutch scholars in the seventeenth century, and argue that it must later passed into local usage. They note, for instance that:

“There is no literary record, however, of the Malay-speaking peoples of the Indonesian archipelago using the term ‘orang utan’ or one of its variants to refer to the ape before the middle of the nineteenth century.

“The web-based Malay Concordance Project, located at the Australian National University, contains many references to ‘orang hutan,’ but before the mid-nineteenth century they all refer, sometimes in a derogatory tone, to human beings who inhabit the forests. . .

“In fact, the first recorded Malay use of a term resembling orang hutan to denote the ape identifies the word as a Western term. The Hikayat Abdullah, written in the 1840s, recounts that ‘The Ruler of Sambas sent Mr. Raffles a present of two apes of the kind which the English call orang-utang.’”

I find it particularly interesting that these scholars found that the earliest Malay-language usage of the term “orangutan” to mean an ape appeared in the Hikayat Abdullah. This work was written by Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, a Melaka-born scholar who was well-versed in Western knowledge and who is credited with starting to transform the intellectual world of Malay-speaking peoples by exposing them to Western ideas.

And while he is famous for having introduced various ideas from the West about governance and society, apparently he also introduced to his readers the “Western” term, “orangutan,” as well.

This gets us back to the “Dutchman.” I have no idea how the proboscis monkey came to be referred to as a “Dutchman,” but after having read about the etymology of the term “orangutan” in Wild Man From Borneo, I’d be willing to guess that it was likewise a complex process.

In the end, what I find significant about all of this is that it shows that the line between “Western” and “indigenous” knowledge is rarely as clear as we often imagine it to be.