The topic of the importance (or non-importance) of South Vietnamese philosopher Lương Kim Định has come up again and this has forced me to think more about this issue.

I have described Kim Định’s scholarship as “bold,” and have tried to define what I mean by that as follows:

“Bold” scholarship is scholarship that presents a new way of looking at something, and which cannot be immediately rejected. “Bad” scholarship is scholarship that can be immediately rejected because it puts forth ideas that scholars already know are not valid. Finally, “bold” scholarship can become “bad” scholarship if scholars can produce evidence to reject it, but that process of producing evidence to reject bold scholarship leads to more sophisticated ideas.

I have also argued that Kim Định’ scholarship should have become “bad” scholarship by now, but people have not rejected it in a convincing way, and as a result, historical scholarship in Vietnam has not been able to benefit from that process of producing evidence to reject bold scholarship.

Finally I’ve also said that this has not happened because people lack the breadth of knowledge that Kim Định had.

Let’s look at some examples of the kind of knowledge that it would take to reject Kim Định’s ideas. To do that we need to remind ourselves of what Kim Định’s basic argument was.

Kim Định argued that in distant antiquity the ancestors of the Việt migrated into the area of China and that later the people whom we refer to as the “Chinese” migrated there as well. The Chinese were pastoralists and violent, and they pushed the Việt southward, and assimilated them as well, until eventually the only remaining Việt group out of what had originally been many related peoples (the “Hundred Việt/Yue”) were those in the Red River delta, that is, the ancestors of the Vietnamese in Vietnam today.

The other point that Kim Định made is that the Việt created many of the ideas that we find in texts like the Yijing (Classic of Changes), but that the Chinese later appropriated these ideas and claimed “authorship” over them. However, he argues that there is a lot of evidence of the ideas in the Yijing in Vietnamese culture, and that this can be seen through the importance of numerology, where numbers like 3 and 4 have deep and significant importance in Vietnamese culture.

Indeed, these concepts, Kim Định argues, form a kind of structure to Vietnamese society, similar to the ideas of structuralism that Claude Leví-Strauss was developing in the field of anthropology around the same time that Kim Định was producing his ideas.

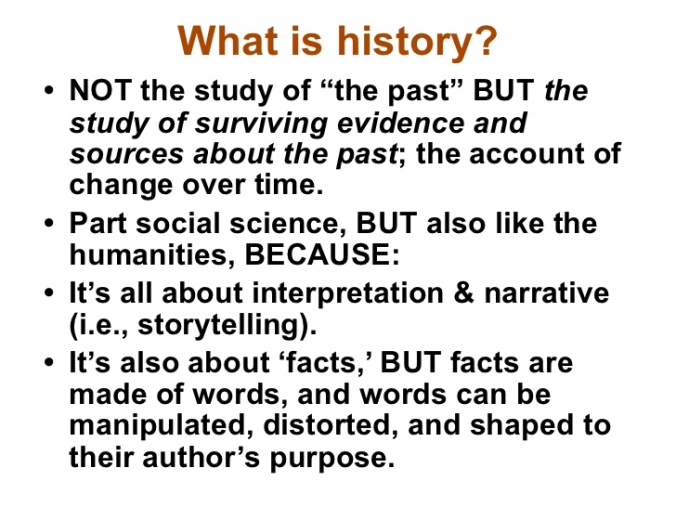

We can call Kim Định’s version of history an “IS” (LÀ) version of history. It is a form of history where history is seen to be true. It’s based on the idea that we can confidently say that something “is” (là) history.

Kim Định tells us, for instance, who the Việt “are” (người Việt “là”) what their history “is” (lịch sử của người Việt “là”) and what the Yijing “is” (Kinh Dịch “là”).

This remains the dominant form of history in Vietnam today, and this is another reason why his ideas have not been rejected, because they are flawed at a conceptual level, and in order to demonstrate those flaws, scholars have to go deeper than simply talking about what history “is.” They need to demonstrate how history is constructed.

This has been an essential part of the historical profession in “the West” ever since the emergence of postmodernism in the 1960s when historians increasingly came to view history as something that is constructed or created rather than simply “is.”

So instead of asking “What is the history of something?” historians in “the West” often ask questions like the following: Where does this information about the past come from? Why does this person think this way? What evidence does s/he base her/his ideas on? How is this person interpreting that evidence, and why is s/he interpreting it in that way? What can this tell us about the past, and what does it tell us about the time when this historian wrote this information?

Let’s now look at Kim Định’s ideas. He presents his ideas as if they “were” (là) historical truth, but where do his ideas come from?

If we look at the historical information that was recorded in Asia prior to the 20th century, we will not find evidence of an ancient Chinese migration into China or of the Chinese pushing a group of people’s known as “the Việt” southward.

So where did Kim Định get those ideas? From Western scholars like Albert Étienne Jean Baptiste Terrien de Lacouperie, Émmanuel-Édouard Chavannes and Leonard Aurousseau who in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries “assumed” that there must have been migrations in antiquity in Asia, and who looked for “evidence” to support these “assumptions” in ancient texts.

Did their “findings” stand the test of time? No, because later generations of scholars asked questions like: Why did this person make this argument? What evidence did he base his ideas on? Is that evidence valid?

How about this idea that there was a large group of related peoples called the “Hundred Việt/Yue” who were all eventually assimilated into the Chinese except for one group? Again, that is something that you will not find discussed in Asia until Western scholars in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries started to look for things like “races” and to try to determine which “races” were able to survive the Social Darwinian struggle between societies.

Here again the ideas that were produced at that time have all been overturned. Now we have studies that argue that ancient Chinese writers constructed an imagined “Other” – the Việt/Yue, and that this image was later appropriated by people like the ancestors of the Vietnamese to label themselves.

Finally there is the topic of the numerology of the Yijing. Much of what Kim Định thought about the Yijing likewise came from his reading of what Western scholars (Joseph Needham, Marcel Granet, Richard Wilhelm, etc.) had said about that text, and it would therefore be important to examine closely what their ideas were and how those ideas may have influenced Kim Định’s thinking.

At the same time, some of Kim Định’s understanding of the Yijing came from what he knew about the long history of employing the numerology of the Yijing in various ways in daily life in Vietnam.

This use of numerology in the Yijing has a history. It is not something that simply “is.” Instead, it is a tradition of ideas that were created/constructed at specific historical times for specific historical reasons.

One of the most important times was during the Song Dynasty period, when Neo-Confucian scholar Shao Yong came up with ideas about how numbers in the Yijing could be used to explain various phenomena in the world. If someone were to examine the history of numerological ideas in East Asia, my suspicion would be that s/he would find that Kim Định wrote about the Neo-Confucian (i.e., Shao Yong’s) version of Yijing numerology and projected that historically-constructed interpretation back into antiquity as an unchanging “truth.” The Yijing “is” (Kinh Dịch “là”). . .

My point here is that Kim Định’s ideas were based on a lot of concepts that he presented as “truth,” but which Western scholars have argued are “constructs,” and often very modern constructs.

Those arguments that Western scholars make, however, have largely been made in the decades since Kim Định published his writings.

Here then is my main point: Given how connected Kim Định was to the Western world of scholarship, and given how so many of the ideas that Kim Định’s work is based on have been discredited in the West in the years since he wrote his books, my argument is that if Vietnamese scholars had continued to be as connected to that scholarly world as Kim Định was and had sought to reject the ideas that Kim Định’s scholarship is based upon by asking the kinds of questions that scholars in “the West” started to ask from the 1960s onward, then the world of historical scholarship in Vietnam today would be much more sophisticated than it is (just as the world of historical scholarship in “the West” is much more sophisticated than it was in the 1960s), and Kim Định would be seen as a catalyst for that positive development.

Why do I say this about Kim Định and not about other scholars? Because, again, I find Kim Định’s scholarship to be “bold,” as it presents a new way of looking at something, and it cannot be immediately rejected.

One main reason why it cannot be immediately rejected is because it is based on a wide range of ideas (i.e., breadth of knowledge). Given that virtually every one of those ideas is flawed in one way or another, it takes a lot of work to challenge Kim Định’s argument as a whole as there are so many issues to address.

Nonetheless, the effort to point out the weakness in the many ideas that Kim Định put forth leads one to think about and find answers to a wide-range of fundamental questions about the past and how we understand it such as the following:

Can we find ethnic groups in antiquity? When was the Vietnamese nation formed? What is the history of Yijing numerology? How did the views of Westerners transform how Vietnamese thought in the 20th century? How does structural anthropology work? Do we have enough information to re-create the structure of an ancient society? Do our current ideas and biases distort what it is that we imagine in the structure of a past society? How do we know any of this? etc., etc.

These questions are all about how history is constructed, and they can lead us to an understanding of how Kim Định constructed history. That process, in turn, can lead to a more sophisticated understanding of the past.

That process, however, still hasn’t taken place in Vietnam.

Instead, history in Vietnam, as it was in Kim Định’s day, still “is.”