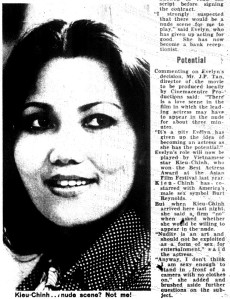

I came across some articles from The Straits Times in 1975 that were talking about a movie that was being made in Singapore at the time called Full House.

Apparently the leading female role was to be played by Evelyn Ai Li, but she gave up the role when she learned that it would require that she “appear in the nude for three minutes.”

Evelyn claims to have been forced to sign her contract before reading the script. However, some of the comments that she made in an interview are a bit contradictory.

At one point she said that “I accepted the part at first because I thought it was a comedy movie without any sexy bits,” whereas at another point she stated that “I strongly expected that there would be a nude scene for me to play.”

Whatever the case may have been, in the end not only did Evelyn give up the part, but she also apparently quit acting and became a bank receptionist.

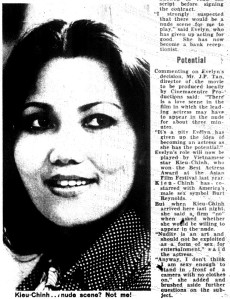

The director of the film, J. P. Tan, was sorry that Evelyn turned down the part, but he welcomed on board South Vietnamese actress Kiều Chinh. However, when Kiều Chinh arrived in Singapore and was asked if she would appear in the nude she responded with an emphatic “No!”

She then went on to say, “Nudity is an art and should not be exploited as a form of sex for entertainment,” and that “Anyway, I don’t think I am sexy enough to stand in front of a camera with no clothes on.”

In the end, I’m not sure what was actually filmed as I can’t find evidence that this movie was ever completed. I found a March 16, 1975 article in The Straits Times which stated that the film was expected to be released in June of that year and that it would “be screened not only in Singapore but in America, Europe, Malaysia and Australia as well.”

However, I haven’t found evidence of this.

The same article reported that “The plot of the film is woven around a $250,000 diamond robbery planned by two men (played by Alan Young and martial arts expert Joey Chen Li) and a woman, Kieu Chinh.”

“The climax of the diamond heist is a thrilling car chase and a shoot-out between the police and the robbers. The law finally catches up and the crooks are killed.”

So if it is true that this movie was never shown, then that would be a shame, as it looks like it must have been really good. . .

In any case, learning about this movie made me want to know more about Kiều Chinh’s career during these years. I found mention in a few places that before 1975 she had “leading roles in 22 features films in Vietnam, India, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Taiwan.”

Her Wikipedia page lists some of these, like the 1972 film, Bão Tình (Storm of Love).

And the 1973 film, Chiếc Bóng Bên Đường (Roadside Shadow)

However, I find it particularly interesting that there was an international dimension to Kiều Chinh’s acting career at that time.

In 1964 she starred in an American movie that was filmed in South Vietnam, A Yank in Viet-Nam.

Then in 1965 she starred with Burt Reynolds in a movie called Operation C.I.A. which was supposed to take place in Saigon, but which was actually filmed in Bangkok.

Finally, in 1970 she made a film with Indian movie star Dev Anand called The Evil Within. Apparently this film was actually made in the Philippines.

While some of these movies might not have been “world-class” (although Kiều Chinh did win some acting awards during this period) they clearly were “international.” It’s amazing to see how much interaction there was at the time in the film world in Asia. It’s also nice to see that Kiều Chinh was at the center of this international cinematic world.

Good job!!